Family caregivers often step into responsibility without guidance, authority, or clear support.

Caregiving is a life — not a role.

This isn’t a wellness moment. It’s just a real one.

“Regulation before resilience.”

Daily maintenance

Because pushing through isn’t the same as being okay.

Cooking helps some people settle their nervous system. You focus on what’s in front of you and nothing else for a minute.

Caregiving isn’t age-restricted. It shows up in classrooms, workplaces, and everyday life for people in their 20s and 30s.

Caregiving happens alongside real life — not instead of it. You’re still in motion.

What Caregiving Actually Looks Like

Young Family Caregivers

Young caregivers are often overlooked. Many are in college, working full-time jobs, or just starting adulthood while also caring for a family member. This responsibility affects their time, finances, relationships, and long-term opportunities. Most didn’t plan for this role, and many navigate it without formal support or recognition. Their caregiving is real, even when the system treats it as invisible.

Necessity Caregiving

Many people become family caregivers not because they planned to, but because there was no other choice. When systems fail, services get denied, or care costs too much, the responsibility falls on whoever is closest. Necessity caregiving often starts suddenly, without training or support, and it rarely has a clear end. Life begins to revolve around medical needs, safety, appointments, and daily survival.

Careers pause or end, plans change, and personal needs move to the background. This kind of caregiving shapes work, housing, finances, and relationships for years. Yet society often treats it as invisible or informal. People take on this role not because they wanted to, but because walking away was never an option.

Mental Disability Caregiving

What mental disability caregiving actually involves

Mental disability caregiving is frequently misunderstood, ignored, or actively weaponized against both the caregiver and the patient. Caregivers are expected to manage safety risks, communication barriers, behavioral instability, and daily functioning while being denied the legal authority needed to secure appropriate care.

The consent and authority gap

When a person lacks the ability to meaningfully consent, access to services often depends on clinical determinations, capacity evaluations, or conservatorship pathways that providers may delay, misinterpret, or fail to initiate altogether. As a result, caregivers are blocked from benefits, programs, and protections the patient otherwise qualifies for, leaving families in prolonged limbo.

How systems mislabel incapacity as refusal

This gap creates sustained trauma—constant advocacy, repeated denial, and the burden of responsibility without authority—while systems frame the situation as “refusal of care” instead of incapacity.

The real-world impact

The failure to properly apply law and policy does not remain administrative; it directly reshapes lives, health outcomes, financial stability, and long-term safety for both the caregiver and the person receiving care.

Where the System Fails Caregivers

Systems often fail caregivers not through a single mistake, but through layers of administrative dysfunction that shift responsibility onto patients and families. Tasks that legally belong to institutions—care coordination, documentation, referrals, and follow-ups—are frequently pushed onto caregivers, even when the patient cannot reasonably manage them. Departments operate in silos, with little communication between medical, behavioral health, insurance, and administrative units, forcing families to repeat the same information without resolution.

Information is often delivered in clinical language, internal codes, or policy references that patients and caregivers are not trained to understand. Instead of explaining options in plain terms, systems rely on jargon, acronyms, and procedural shorthand, making it unclear what is being offered, denied, or delayed. When caregivers ask for clarification, the lack of transparency is framed as “policy” rather than acknowledged as a communication failure.

In many cases, laws and policies designed to protect patients are selectively interpreted or used defensively to limit responsibility. Capacity, consent, and eligibility standards are applied inconsistently, allowing systems to label situations as “noncompliance” or “refusal” instead of addressing underlying incapacity or access barriers. This weaponization of policy leaves caregivers carrying accountability without authority.

What looks like individual confusion is often structural design. The messiness is not accidental—it’s the result of fragmented systems that rely on patients and caregivers to absorb gaps, delays, and contradictions. Over time, this creates exhaustion, mistrust, and long-term harm, especially for families already navigating disability, trauma, and unequal access to resources.

Caregivers Being Whole Humans

Family caregivers, especially in mental disability caregiving, don’t “clock out.”

They live inside the care—inside the appointments, the crises, the paperwork, the safety planning, and the constant vigilance that people only notice when something goes wrong. And when the person you’re caring for can’t consistently understand, consent, or follow through, the system often turns that reality into a technicality: everything still hinges on consent.

If providers don’t complete or document capacity evaluations, don’t initiate the right clinical determinations, or don’t support the legal pathways that match the patient’s functioning, families get stuck in a harmful loop—labeled as “refusal” or “noncompliance” while the caregiver is carrying protective supervision with no authority and no relief.

This gap blocks treatment, delays stability, and can even keep caregivers from accessing pay or benefits tied to supervision and eligibility—so you end up losing your job, losing time, and losing years, while being treated like the problem is administrative.

That’s the reality for a lot of families: responsibility without recognition, accountability without authority, and a system that acts like the caregiver is optional when the care is not.

The system explained like you’re human

Instead of guiding families, the system breaks care into pieces that don’t talk to each other. Caregivers are left to interpret policies, track paperwork, and push things forward without authority. Laws meant to protect patients can end up delaying care or shifting responsibility onto families.

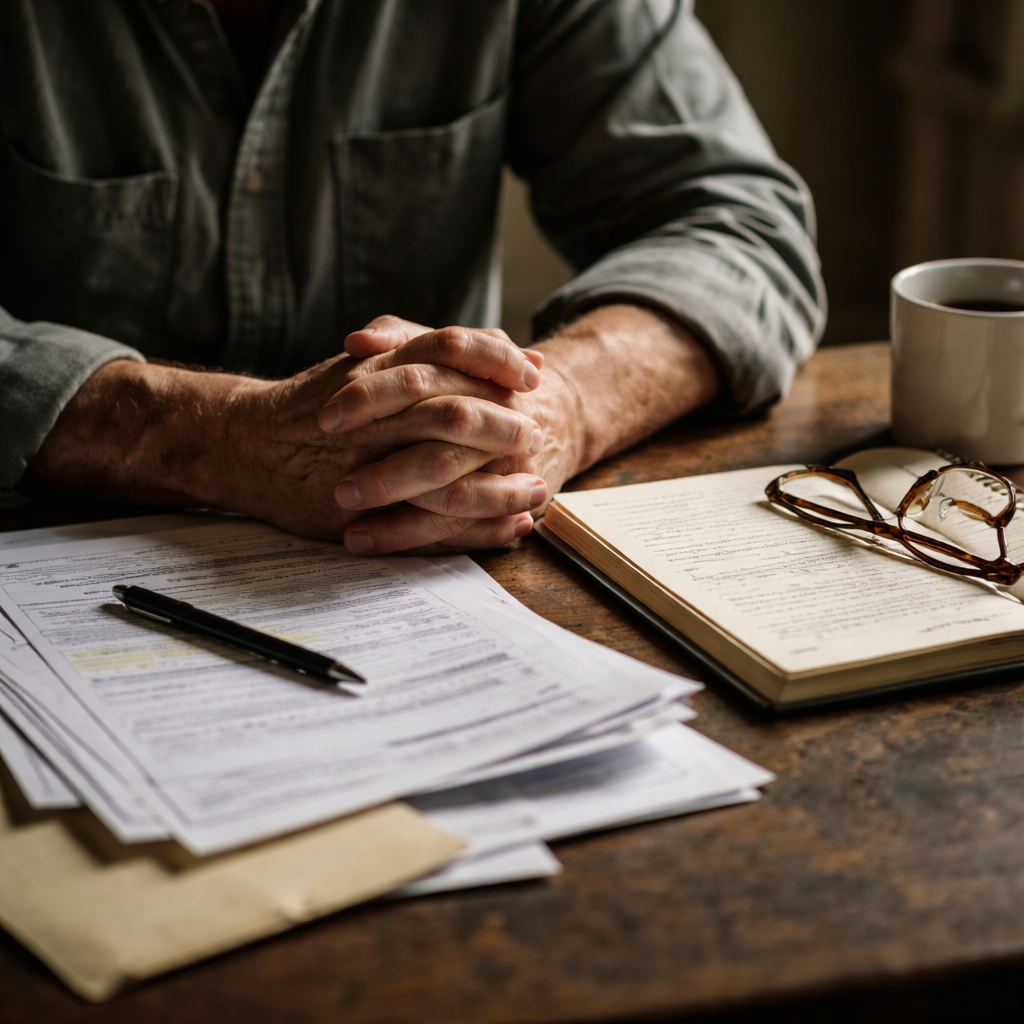

Tools we actually use

These are the tools family caregivers rely on every day—binders, notebooks, calendars, phones on speaker, and stacks of paperwork that never fully disappear. They aren’t organizational hobbies; they’re survival systems built to track appointments, document failures, remember names, and hold institutions accountable. When the system doesn’t coordinate care, caregivers create their own tools just to keep things from falling apart.

Getting Medication Started With Schizophrenia

Why is getting someone with schizophrenia on medication so hard—especially when everyone keeps saying it shouldn’t be?

We were told what should work, but none of it matched what was actually happening day to day. What finally helped us wasn’t force, pressure, or compliance—it was changing how we approached medication in the very beginning. This is what worked for us during that early window, before things became more complicated.

Tools we wish someone handed us earlier

Most family caregivers begin by trusting that doctors, providers, and systems will do what they’re supposed to do. You assume someone will explain the process, flag important decisions, and tell you what rights, protections, or timelines matter. What many caregivers don’t realize is how much depends on information you were never given—laws about consent and capacity, policies that affect eligibility, and protections you need to secure early for yourself and the person you’re caring for. By the time you learn these things, it’s often because something has gone wrong: care is delayed, benefits are denied, or you’re being told it’s too late to fix. Looking back, so many caregivers realize that what they lacked wasn’t effort or advocacy—it was access to information the system never made clear.

What we lacked wasn’t effort or advocacy — it was information the system never made clear.

13 Things I Wish I Knew When I Became a Family Sibling Caregiver →

You don’t have to do life alone. Pull up. Stay a minute. Take what you need.

Get Yelloux Cove by email

If you want to hear when new free tools, programs, or support drops — this is how it happens. We don’t email a lot. We only show up when there’s something worth your time.